A German song Mahmoud had never heard before played on the radio of the van that took him and his family through the streets of Berlin. The capital of Germany was the biggest city he had ever seen, far bigger than Aleppo. It was filled with nightclubs and cafés and shops and monuments and statues and apartments and office buildings. Almost all the signs were in German, but here and there he saw a sign in Arabic advertising a clothing store or a restaurant or a market. Buildings lined the sidewalks like ten- story walls of brick and glass, and cars and bicycles and buses and trams rattled and honked and clanged by in the streets.

This strange, frightening, exciting place was to be Mahmoud’s new home.

The German government had taken in Mahmoud and his family. For the past four weeks the four of them had lived in a school in Munich that had been turned into simple but clean housing for refugees. They had stayed there—free to come and go as they pleased—until a host family agreed to let them share their home while Mahmoud’s parents got on their feet.

A host family here, on this street, in the capital of the country.

The van pulled up to the curb outside a little green house with white shutters and an A-frame roof. Flowers filled the window boxes like Mahmoud had seen in Austria, and two German cars were parked in the driveway. Across the street in a park, teenagers did tricks on skateboards.

Mahmoud’s father slid open the side door for them to climb out, and Mahmoud and his mother and brother grabbed the backpacks filled with the clothes, toiletries, and bedrolls the German relief workers had given them.

The relief worker who’d driven them led Mahmoud’s mother and father and brother up the steps to the front door of the little house, but Mahmoud stood for a moment on the sidewalk, looking around at the neighborhood.

Mahmoud knew from his history class back in Syria that Berlin had been all but destroyed by the end of World War II, reduced to a pile of rubble like Aleppo was now. Would it take another seventy years for Syria to return from the ashes the way Germany had? Would he ever see Aleppo again?

Cries of joy and welcome came from the porch, and Mahmoud followed his family up the steps. His mother was being hugged by an elderly German woman, and an elderly German man was shaking hands with his father. The German relief worker had to translate everything everyone said to each other. Mahmoud and his family didn’t speak German yet, and the family apparently didn’t speak any Arabic. The German family had at least managed a sign written in Arabic that said WELCOME HOME on it, even if the expression they had used was a bit formal. Mahmoud still appreciated the effort—it was better than he could do in German.

The man shaking hands with his father turned to Mahmoud and Waleed, and what Mahmoud saw surprised him. He was a really old man! He had wrinkly white skin and thin white hair that stuck out a bit on the sides, like he’d tried to comb it but it wouldn’t stay put. When the relief worker had

told them they’d be staying with a “German family,” Mahmoud had imagined a family like his own, not like his grandparents.

“His name is Saul Rosenberg,” the relief worker translated, “and he says welcome to your new home.” As Mahmoud shook the old man’s hand, he spotted a small, thin, ornate wooden box attached to the frame just outside the front door. Mahmoud recognized the symbol on the box—it was the Star of David! The same symbol on the flag of Israel. Mahmoud tried not to show his surprise. Not only was this couple old, they were Jewish! Back in the Middle East, Mahmoud knew, Jews and Muslims had been fighting each other for decades. This was a strange new world.

Herr Rosenberg’s wife broke away from Mahmoud’s mother and bent down to say hello. She was a wide woman, white-haired like her husband, with big round glasses and a gap-toothed, friendly smile. From the pockets of her frock she withdrew a little stuffed rabbit made of white corduroy and offered it to Waleed. His eyes lit up as he took it from her.

“Frau Rosenberg made it herself. She’s a toy designer,” the translator explained.

The old woman said something, directly to Mahmoud.

“She says she would have made one for you too,” the translator said, “but she thought you might be too old for stuffed animals.”

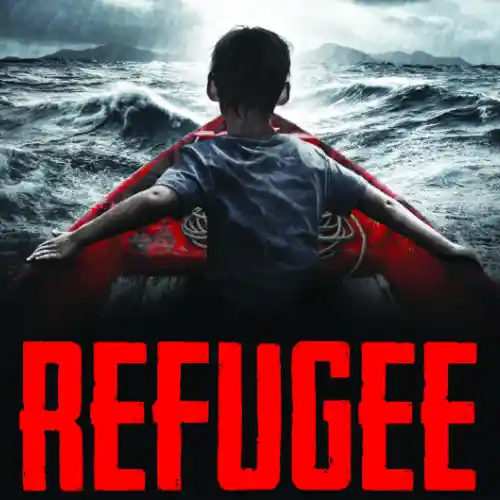

Mahmoud nodded. “She can make one for my little sister, though, when we find her,” he told the relief worker. “We had to hand her off to another boat to save her when we were drowning in the Mediterranean Sea. It was my fault. I’m the one who told my mother to do it, and now I have to find her and bring her back.”

Frau Rosenberg looked questioningly at the relief worker as he translated, and her bright smile faded. Waleed ran off to show his mother

his new toy, and the old woman led Mahmoud into the hallway just inside the house, where family pictures hung on the wall.

“I was a refugee once, just like you,” the old woman said through the interpreter, “and I lost my brother.” She pointed to an old brown photograph in a picture frame, of a mother and father and two children: a boy about Mahmoud’s age in glasses, and a little girl. The father and son wore suits and ties, and the mother wore a pretty dress with big buttons. The girl was dressed like a little sailor. “That’s me there, the girl. That’s my family. We left Germany on a ship in 1939, trying to get to Cuba. To escape the Nazis. I was very little then, and I’m very old now, and I don’t remember too much about that time. But I do remember my father being very sick. And a cartoon about a cat. I remember that. And a very nice policeman who let me wear his hat.

“My father was the only one to make it to Cuba. He lived there for many years, long after the war, but I never saw him again. He died before we could find each other. The rest of us couldn’t leave the ship with him. And no other country would take us. So they brought us back to Europe just in time for the war. Just in time to go on the run again.

“The Nazis caught us, and they gave my mother a choice—save me, or save my brother. Well, she couldn’t choose. How could she? So my brother chose for her. His name was Josef.” Mahmoud watched as she reached out and gently touched the boy in the photograph, leaving a smudge on the glass. “He was about your age, I think. I don’t remember much about him, but I do remember he always wanted to be a grown-up. ‘I don’t have time for games,’ he would tell me. ‘I’m a man now.’ And when those soldiers said one of us could go free and the other would be taken to a concentration camp, Josef said, ‘Take me.’

“My brother, just a boy, becoming a man at last.”

She paused a moment, then took the picture down off the wall reverently, with both hands.

“They took my mother and my brother away from me that day, and left me alone there in the woods. I only survived because a kind old French lady took me in. She told the next Nazis who came knocking that I was family.

When the war was over and I was old enough, I came back here, to Germany, to look for my mother and brother. I searched for them a long time, but they had died in the concentration camps. Both of them.” The woman drew a breath. “I only have this picture of them because a cousin kept it, a cousin who was hidden away by a Christian family throughout the war. Here in Germany I met my husband, Saul. He had also survived the Holocaust. We stayed because he had family here. And we made a family of our own,” Frau Rosenberg said. She spread her arms wide and turned in the little hallway, showing Mahmoud the dozens of pictures of her children and grandchildren and great-grandchildren. She put her hand to the old yellowed picture of her family again.

“They died so I could live. Do you understand? They died so all these people could live. All the grandchildren and nieces and nephews they never got to meet. But you’ll get to meet them,” she told Mahmoud. “You’re still alive, and so is your little sister, somewhere. I know it. You saved her. And together we’ll find her, yes? I promise. We’ll find her and bring her home.”

Mahmoud started to cry, and he turned away and tried to blink back his tears. The old Jewish woman put her arms around him and pulled him into a tight hug.

“Everything’s going to be all right now,” she whispered. “We’ll help you.”

“Ruthie, komm hier,” Frau Rosenberg’s husband called to her. Mahmoud didn’t need the translator to tell him that Herr Rosenberg wanted them to

join him in the living room.

Mahmoud dragged a sleeve across his wet eyes, and Frau Rosenberg tried to hang the picture back on the wall. Her old hands were too shaky, though, and Mahmoud took it from her and hung it back on its nail for her.

His gaze lingered on the picture. He was filled with sadness for the boy his age. The boy who had died so Ruthie could live. But Mahmoud was also filled with gratitude. Josef had died so Ruthie could live, and one day welcome Mahmoud and his family into her house.

The old woman gave Mahmoud’s arm a squeeze, and she led him into the living room. Mom and Dad were there, and Waleed and Herr Rosenberg, and the space was bright and alive and filled with books and pictures of family and the smell of good food.

It felt like a home.