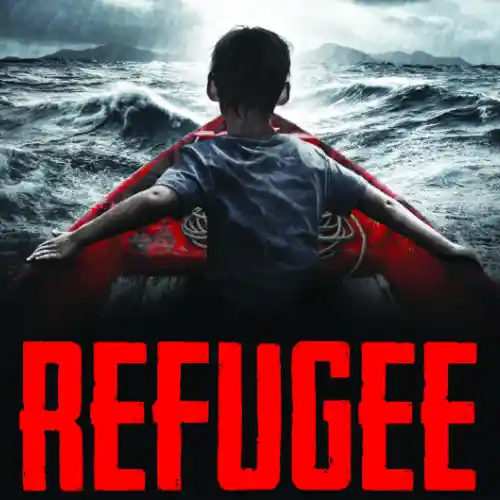

Mahmoud was in and out of sleep, waking every few seconds when the waves washed over him. Minutes—hours?—passed, and Mahmoud dreamed that a boat was coming for them. He could hear its motor over the lapping of the waves.

Mahmoud jerked awake. He ran a wet, cold hand down his face, trying to focus, and he heard it again—the sound of a motor. He wasn’t dreaming!

But where was it? The rain had stopped, but it was still dark. He couldn’t

see the boat, but he could hear it.

“Here!” he cried. “Here!”

But the sound of the motor still stayed frustratingly, agonizingly, far away. If only whoever was on the boat could see him, Mahmoud thought.

All his life he’d practiced being hidden. Unnoticed. Now, at last, when he most needed to be seen, he was truly invisible.

Mahmoud cried in exhaustion and misery. He wanted to do it all over again. He wanted to go back and stand up for the boy in the alley in Aleppo who was getting beaten up for his bread. To scream and yell and wake the

sleeping citizens of Izmir so they would see him and all the other people sleeping in doorways and parks. To tell Bashir al-Assad and his army to go to hell. He wanted to stop being invisible and stand up and fight. But now he would never get a chance to do any of that. It was too late. There was no time.

Time. The phone! Mahmoud still had the phone in his pocket! He pulled it out and pushed the button on it through the plastic bag, and the screen with the clock on it lit up like a beacon in the night. Mahmoud held it over his head and waved it in the dark, screaming and yelling for help.

The motor got louder.

Mahmoud wept for joy as a boat emerged from the darkness—a real boat this time, not a dinghy. A speedboat with lights and antennas and blue and white stripes on the side—the colors of the Greek flag.

A Greek Coast Guard ship, come to save them.

And on the front of the ship, down on his knees with hands clasped in thanks, was Mahmoud’s father.

Waleed was there too, in the back under a foil thermal blanket, and soon Mahmoud and his mother were out of the water and wrapped in the foil blankets too, what little body heat they still had left reflected back at them.

Mahmoud’s mother was too insensible to speak, so Mahmoud told his father how they had given Hana away rather than see her drown with them.

Mahmoud’s father wept, but pulled Mahmoud to him and hugged him.

“Hana’s not with us, but she’s alive. I know it,” his father told him.

“Because of you, my son.”

The Greek Coast Guard boat swept through the choppy Mediterranean the rest of the night, pulling more people out of the water. The Coast Guard finally set Mahmoud and his family and all the other refugees down on the island of Lesbos. It was almost six o’clock in the morning, and the sky was

beginning to lighten with the dawn. Mahmoud wasn’t sure, but he thought he and his mother had spent more than two hours in the water.

When they stepped off the boat, Mahmoud’s father got down on his hands and knees and kissed the ground and gave thanks to Allah. It was time for morning prayers anyway, and Mahmoud joined him. When they were finished, Mahmoud staggered up the rocky gray shore, squinting at the hills that rose just beyond the beach. Then he realized: They weren’t real hills.

They were piles and piles of life jackets.

There were mountains of them, stretching up and down the coast as far as Mahmoud could see. The way Aleppo had its piles of rubble, Lesbos had its piles of life jackets, abandoned by the hundreds of thousands of refugees who had come before them, shedding the vests they no longer needed and moving along on the road to somewhere else.

There were bodies on the beach too. People who hadn’t survived the sea in the night, who hadn’t been found by the Coast Guard in time. Men, mostly, but a few women too. And a child.

Mahmoud’s mother rushed to the infant, howling Hana’s name.

Mahmoud hurried after her, horrified, but the child wasn’t Hana. It was someone else’s baby daughter, her lungs filled with seawater. Mahmoud’s mother cried into his shoulder until a Greek man in a uniform moved them both away from the body and recorded the infant in a little notebook.

Tallying the daily dead. Mahmoud staggered away, feeling as numb as if he were in the freezing water again.

Mahmoud’s mother went to all the other refugees who had landed in the night and were still there, asking each of them if they had seen her little Hana. But none of them had. The boat with Mahmoud’s little sister on it

was gone—it had either reached the island and its passengers had already moved on, or it too had wrecked on the rocks.

Mahmoud’s mother fell to her knees on the rocky ground and wept, and Mahmoud’s father held her close and let her cry.

Mahmoud felt gutted. It was all his fault. Hana might still be with them if he hadn’t gotten someone on that boat to take her. Or she might have died

during their two hours in the water.

Either way, they had lost her.

“Mahmoud,” his father said quietly over his sobbing mother, “check the other bodies and see if they have any shoes that will fit us.”