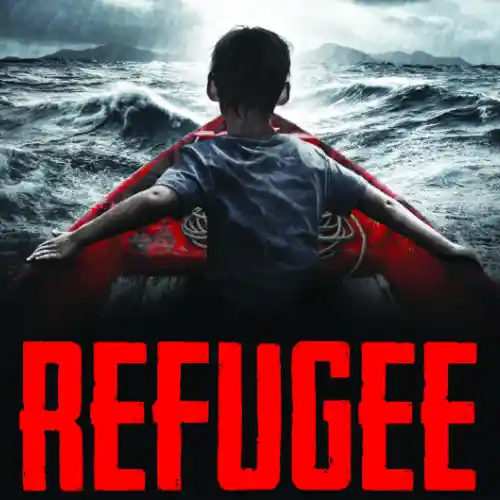

Here, in this boat that had been her home for four days and four nights, Isabel’s little brother was born.

Not right away. First had come her mother’s frantic pushing, pushing, pushing to bring the baby into the world, while the rest of them paddled, paddled, paddled. All but Señora Castillo, who sat on the bench next to Mami, holding her hand and talking her through it. Behind them, the Coast Guard had finished picking up Isabel’s grandfather and was headed their way, lights flashing.

Their little blue boat was close to the shore. The waves around them were breaking with white caps. Isabel could see people dancing on the beach. But they weren’t close enough. Weren’t going to make it. That’s when Mami’s cries had mixed with Amara’s yell to “Swim for it!” and Luis and Amara hopped over the side, half swimming, half tumbling toward shore.

“No, wait!” Isabel cried. Her mother couldn’t swim for the beach. Not like this. They had to paddle in or her mother would never make it to the US.

Isabel and Papi and Señor Castillo rowed as hard as they could, but the Coast Guard ship was faster. It was going to catch them.

“Go!” Isabel’s mother told her husband between pants. “If you’re

caught, they’ll send you back.”

“No,” Papi said.

“Go!” Mami said again. “If I’m caught, they’ll just—they’ll just send me back to Cuba. Go, and take Isabel. You can—you can send money, like you always planned!”

“No!” Isabel cried, and amazingly, her father agreed.

“Never,” he insisted. “I need you, Teresa. You and Isabel and little Mariano.”

Isabel’s mother sobbed at the name, and tears sprang to Isabel’s eyes too.

Like the boat, they had never settled on a name for the baby. Not until now.

Naming the baby after Lito was the perfect way to remember him, no matter where they were.

“But they’ll send us back,” Mami sobbed.

“Then we’ll go back,” Papi said. “Together.”

He put his forehead to his wife’s temple and held her hand, taking Señora Castillo’s place as Mami made her last push.

The Coast Guard ship bounced in the waves. It was almost on top of them.

“It’s time!” Señor Castillo said. “We have to swim for it. Now!”

“No, please,” Isabel begged, paddling helplessly against the tide, tears running down her face. They were so close. But Señor Castillo was already helping his wife over the side into the water.

They were abandoning ship.

Isabel’s mother cried out louder than before, but Papi was with her. He would take care of her. All that mattered now was rowing. Rowing as hard

as Isabel could. She was her mother’s last hope.

“Take—take Isabel with you,” she heard her mother say between pushes.

But Isabel wasn’t worried. She knew her father wouldn’t listen. That he would never leave. Neither of them would. They were a family. They would be together. Forever.

But then suddenly arms were picking her up, lifting her over the side!

“Say good-bye to Fidel,” Señor Castillo said. He was the one Mami had been talking to. He had come back, and he was the one lifting Isabel out of

the boat and into the water!

“No—no!” Isabel cried.

“You saved my life once, now let me save yours!” Señor Castillo told her.

Isabel didn’t listen. She kicked and screamed, trying to get free. She didn’t want to go to the States if it meant leaving her parents—her family— behind. But Señor Castillo was too strong. He tossed her in the water, and she sank under the waves in a tangle of arms and legs and bubbles before quickly hitting bottom.

Isabel found her footing and pushed herself back up out of the water. It was chest deep, and the waves that slid by her toward shore lifted her up and set her down again on the sand. Iván’s cap had come off her head in her splashdown, and she snatched it up before it disappeared in the surf.

Then she grabbed the side of the boat to climb back in.

Señor Castillo’s arm went around her waist and pulled her away.

“No!” Isabel cried. “I won’t leave them!”

“Hush! We’re not going anywhere,” Señor Castillo said. “Help us pull the boat to shore!”

Isabel looked around, and for the first time she saw that Señora Castillo was still there, and Luis and Amara were there too. They all stood waist-

deep in the water around the boat. They had come back!

They all found somewhere to grab on to the boat and pull, churning up the sand at their feet. Isabel sobbed with relief and grabbed hold. It was harder for her to pull when the waves kept lifting her, but the sight of the Coast Guard boat bearing down on them helped motivate her.

So did the cheering.

The other refugees on the Coast Guard ship were hopping up and down and clapping and yelling encouragement, just like the crowd on the beach had when they’d left Havana. Isabel saw her grandfather running up and down the ship, waving them toward shore like a baseball player urging a home run ball around the foul pole. She laughed in spite of herself. The water was just below Isabel’s waist. They were almost there!

The Coast Guard ship cut its engines to run up to them, and that’s when Isabel heard her baby brother cry out for the first time.

The sound stunned Isabel and the others into stillness. It took her father a moment to cut the umbilical cord with his pocket knife. Then he stood up in the boat with something tiny and brown, staring down at it like he held the world’s most incredible treasure in his arms. Isabel gaped. All this time, she had known her mother was having a baby. Isabel had seen plenty of babies before. They were cute, but nothing special. But this—this wasn’t just a baby. This was her brother. She had never met him before this moment, but she loved him now with a deepness she had never felt before, not even toward Iván. This was Mariano, her little brother, and she suddenly wanted to do anything and everything she could to protect him.

Papi finally looked up from his newborn son. “Help me get Teresa out of the boat,” he told the others.

The Coast Guard ship was almost alongside the boat, and the adults scrambled for the other side.

Papi bent down over the bow and held out her crying baby brother to Isabel. As if in a dream, Isabel’s arms reached up and took him. He was covered with something slimy and gross and was screaming like somebody had slapped him, but he was the most amazing thing Isabel had ever seen.

Little Mariano.

Isabel hugged him protectively against the push and pull of the waves.

He was so tiny! So light! What if she stumbled? What if she dropped him?

How could her father have put something so new, so precious, in her arms?

But then she understood—Isabel had to carry little Mariano to shore so her father and the others could carry Mami behind them.

“Go, Isabel,” her father told her, and she went.

Isabel held the baby up high to keep him out of the waves that pushed them both to shore, stumbling as the water crashed against the back of her legs, but step by step she staggered up onto the beach.

Onto United States soil.

Isabel turned in the sand, soaking wet and exhausted, to look behind her.

Papi and Amara and the Castillos were on their feet, carrying Isabel’s mother through the shallow water, where the Coast Guard boat couldn’t go.

The ship had cut its lights and was backing out to sea. On the rear of the boat, among the waving, cheering refugees, was Isabel’s grandfather.

Isabel held the screaming baby up high for him to see, and Lito fell to his knees, hands clasped to his chest. Then the engines roared, the sea churned, and the Coast Guard ship disappeared out to sea.

The Castillo and Fernandez families helped each other up onto the sandy beach, and their wet feet became dry feet. Señor Castillo fell to his knees and kissed the ground.

They had made it to the States. To freedom.

Still in a dream, Isabel wobbled up the sand toward the flashing lights and thumping music and dancing people. She stepped into the light, and the music stopped and everyone turned to stare. Then suddenly people were running to help her and her family.

A tan young woman in a bikini dropped into the sand beside Isabel.

“Oh, my God, chiquita,” she said in Spanish. “Did you just come off a boat? Are you Cuban?”

“Yes,” Isabel said. She was trembling, but she clung to Mariano like she would never let him go. “I’m from Cuba,” Isabel said, “but my little brother was born here. He’s an American. And soon I will be too.”