Certainly there was something suspicious in his granting us these privileges. But all I felt was numb, resigned, sitting in that stuffy office. Not only was there nothing in the world we could do to save the men, there was nothing in the world we could do to save ourselves either.

Talk of the people, Voice of God

November 25, 1960

The soldier was standing on the side of the road with his thumb out, dressed in a camouflage uniform and black, laced-up boots. The sky was low with clouds, a storm coming. On this lonely mountain road, I felt sorry

for him.

“What do you say?” I asked the others.

We were evenly divided. I said yes, Mate said no, Patria said whatever.

“You decide,” we told Rufino. He was fast becoming our protector and guide. None of Bournigal’s other drivers would take us over the pass.

Mate had grown suspicious of everyone since Tio José’s visit. “He is a soldier,” she reminded us. On my side of the argument I added, “So? We’ll be all the safer.”

“He’s so young,” Patria noted as we approached the shoulder where he stood. It was just an observation, but it tipped the scales, and Rufino stopped to offer the boy a ride.

He sat in front with Rufino, twisting his cap in his hands. The uniform was too large, and the starched shoulders stuck out in crisp, unnatural angles. For a minute, it worried me that he seemed so uncomfortable, maybe he was up to something. But as I studied the closely cropped head and the boyish slenderness of his neck, I decided he was just not used to

riding around with ladies. So I made conversation, asking him what he thought of this and that.

He was headed back to Puerto Plata after a three-night furlough to meet his newborn son in Tamboril. We offered him our congratulations, though I thought he was much too young to be a father. Or a soldier, for that matter.

Someone was going to have to take in that uniform. Maybe we could do alterations in our new shop.

I remembered the camouflage fatigues I’d sewn for myself last November. Ages ago, it seemed now. The exercises I used to do to get in shape for the revolution! Back then, we believed we’d be in these mountains as guerrillas before the year was over.

And here it was late November, a year later, and we were riding over the pass in a rented Jeep to visit our husbands in prison. The three butterflies, two of them too skittish to sit next to the windows facing the steep drop just inches from the slippery road. One of them, just as scared, but back to her old habits of pretending there was nothing to fear, as el señor Roosevelt had said, but being afraid.

I made myself look down the side of the mountain at the gleaming rocks below. The dangerous possibilities, the fumes from the bad muffler, the bumpiness of the road—I felt a queasiness in my stomach. “Give me one of those Chiclets, after all,” I asked Mate. She’d been chomping on hers ever since we started to climb the mountain on this curving stretch of road.

It was our fourth trip to see them since their transfer to Puerto Plata. We had left the children home this time. They’d already been on the previous Friday to see their daddies, and every one of them had gotten car sick on the way there and back. This mountain road made everyone queasy.

“Tell me something,” I asked the young soldier in the front seat. “What’s it like being posted in Puerto Plata?” The fort there was one of the biggest, most strategic in the country. Its walls stretched out gray and ominous for miles, and its spotlights beamed even into the Atlantic. It was a popular coast for invasions, therefore heavily guarded. “Have you seen any action yet?”

The young soldier half turned in his seat, surprised that a woman should interest herself in such things. “I just joined last February when the call went out. So far I’ve only done prison detail.”

I exchanged a glance with my sisters in the back seat. “You must get some important prisoners from time to time?”

Patria dug her elbow in my ribs, biting her lip so as not to smile.

He nodded gravely, wanting to impress us with his own importance as their guard. “Two politicals came just this last month.”

“What’d they do?” Mate asked in an impressed voice.

The boy hesitated. “I’m not really sure.”

Patria took both Mate’s and my hands in her own. “Are they going to be executed, you think?”

“I don’t believe so. I heard they were going to be moved back to the capital in a few weeks.”

How odd, I thought. Why go to all the trouble of transferring the boys up north only to ship them back in a month? We had already decided on moving to Puerto Plata and opening a store, and this news would ruin that plan. But then, this was just a boy in a too-big uniform. What did he know?

The storm started up about then. Rufino let down the canvas flaps and told the soldier how to do his side. We snapped the back panels in place. The inside of the Jeep grew dark and stuffy.

Soon the downpour was upon us. The heavy rain hit the canvas top with the sound of slaps. I could barely hear Patria or Mate talking, much less Rufino and the young soldier up front.

“Maybe we should think it over,” Patria was saying.

Before our prison visit today, we had planned to look at some rental houses Manolo’s friend Rudy and his wife Pilar had lined up for us. It had all been decided. We would be moving to Puerto Plata with the children by the first of December, opening up a little store at the front of the house. The reaction to our traveling had finally become too disturbing. Every time we left the house, people came out on the road and blessed us. When we got back, we felt obliged to blow the horn, as if to say, “We’re here, safe and sound!”

Dedé and Mamá got weepy every time we started out.

“Those are just rumors,” I’d say, trying to comfort them.

“Talk of the people, voice of God,” Mama would answer, reminding me of the old saying.

“Rufino, if it’s too bad, and you want to stop—” Patria had come forward in her seat. We could see that there was nothing to be seen out the front but sheets of water. “We can wait till the storm’s over.”

“No, no, don’t preoccupy yourselves.” Rufino was almost shouting to be heard above the pounding rain. Somehow, a yelled reassurance did not sound very reassuring. “We’ll be in Puerto Plata by noon.”

“Si Dios quiere,” she reminded him.

“Si Dios quiere, he agreed.

It was reassuring to see the young soldier’s head nod in agreement—until he added, “God and Trujillo willing.”

This was Patria’s first visit to see Manolo and Leandro since they’d been moved. Usually, on Thursdays, she was headed down to La Victoria to visit Pedrito with a regular ride that didn’t return until Friday midday. By that time Mate and I had already left for Puerto Plata, accompanied by one or the other of our mothers-in-law. Since the rumors had gotten so bad, both of them had virtually moved in with us. Their sons had made them promise they wouldn’t let us out of their sight. Those poor women.

The night before, Mate and I had been readying ourselves for our trip today, talking away, just the two of us. Patria was still in the capital, and Dedé’s little one was sick, and so she was home, taking care of him. Mate was doing my nails when we heard the sound of a car pulling into the driveway. Mate’s hand jerked, and I could see that she had painted the whole top of my thumb red.

We both tiptoed down the hall to the living room and found Mamá angling the jalousie just so. We all sighed with relief when we heard Patria’s voice, thanking her ride.

“And what are you doing traveling at this time of night!” Mama scolded before poor Patria was even in the door.

“I got a ride back tonight with Elsa,” Patria explained. “There were five already in the car. But she was nice enough to squeeze me in. I’ve been wanting to go see the boys.”

“We’ll discuss that in the morning,” Mamá said in her nonnegotiable voice, herding us out of the room by flipping off the lights.

In our bedroom, Patria was full of talk about Pedrito. “Ay, Dios mío, that man was so romantic today.” She raised her arms over her head and stretched in that full-bodied way of cats.

“iEpa!” Mate egged her on.

She smiled a pleased, dreamy smile. “I told him I wanted to see the boys tomorrow, and he gave me his permission.”

“Patria Mercedes!” I was laughing. “You asked for his permission? What can he do from prison to stop you?”

Patria gave me a quizzical look, as if the answer were obvious. “He could have said, no, you can’t go.”

Next morning, we had Mama almost convinced that the three of us would be just fine traveling by ourselves when Dedé rushed in, breathless. She looked around at the signs of our imminent departure. Her eye fell on Patria, putting on her scarf. “And what are you doing here?” she asked.

Before Patria could explain, Rufino was at the door. “Any time you ladies are ready. Good day,” he said, nodding towards Mama and Dedé. Mama murmured her good days, but Dedé gave the chauffeur the imperious look of a mistress whose servant has disobeyed her wishes.

“All three of you are going?” Dedé was shaking her head. “What about Dona Fefita? Or Dona Nena?”

“They need a rest,” I said. I didn’t add that we’d be house-hunting today.

We hadn’t told our mothers-in-law or Mama or—Lord knows!—Dedé about our plans yet.

“Why, Mama, with all due respect, are you mad to let them go alone?”

Mamá threw up her hands. “You know your sisters,” was all she said.

“How handy,” Dedé said with heavy sarcasm, pacing the room. “How very very handy for the SIM to have all three of you sitting pretty in the back seat of that rundown Jeep with a storm brewing in the north. Maybe I

should just give them a call. Why not?”

Rufino was at the door again.

“We should go,” I said, to spare him having to say it again.

“La bendición,” Patria called, asking for Mama’s blessing.

“La bendicón, mis hijas. Mama turned abruptly, as if to hide the worry on her face. She headed towards the bedrooms. As we went out, I could hear her scolding the children, who were wailing with disappointment at not being taken on our outing.

Dedé stood by the Jeep, blocking our way. “I’m going crazy with worrying. I’ll be the one locked up forever, you’ll see. In the madhouse!”

There was no self-mockery in her voice.

“We’ll come visit you, too,” I said, laughing. But then seeing her teary, unhappy face, I added, “Poor, poor Dede.” I took her face in my two hands.

I kissed her goodbye and then climbed into the Jeep.

We were at the counter paying for the purses. The very correct young salesclerk was taking his time, and the manager had already been by once to hurry him along. With infinite patience the clerk folded the straps just so, located each purse at the center of the brown parcel paper he painstakingly tore from the roll, and commenced creasing the edges. I watched his hands working, mesmerized. This must be how God does things, I thought, as if He has all the time in the world.

We had asked permission for this brief detour to El Gallo on our way to Puerto Plata today. Our sewing supplies were low again, and we needed thread in several colors, seam bindings, and ribbons to complete November’s orders. The drive over the mountain was long. If our nerves cooperated, we could catch up on some of the hand sewing today.

When we went to pay, the salesclerk showed us a new shipment of Italian purses. Mate mooned over one in red patent leather with a snap in the shape of a heart. But of course, she wouldn’t think of such an extravagance.

“Unless—” She looked up at us. Patria and I were also examining the display case. There was a practical black bag with innumerable zippered pockets and compartments just perfect for Patria’s goodwill supplies. Then I spotted a smart leather envelope that would be exactly the thing for a young lawyer to carry. An investment in hope, I thought.

“Shall we?” We looked at each other like naughty schoolgirls. We hadn’t bought ourselves a single thing since before prison. We should, Mate decided. She did not want to be the only one splurging. I didn’t need much talking into, but at the last minute, Patria desisted. “I just can’t. I don’t really need it.” I felt a flicker of anger at her for her goodness that I didn’t want—at this moment—to live up to.

As he wrapped Mate’s first, the man kept his head bowed. But for one fleeting instant, I caught his eyes on us and a look of recognition dawning on his face. How many people—on the street, in church, on the sidewalks, in shops like this one—knew who we were?

“New purses. A sign of good luck coming!” Somebody else waiting for the future, I thought. I felt a flush of embarrassment to be caught shopping when I should have been plotting a revolution.

Rufino came in the store from the sidewalk where he was parked. “We better get started. The rainstorm looks like it’s coming and I want to be over the worse part of the pass by then.”

The young man looked up from his wrapping. “You aren’t planning to go over the pass today, are you?”

My stomach clenched. But then, I thought, the more people know, the better. “We always go Fridays to Puerto Plata to see the men,” I told him.

The floor manager came forward, smiling falsely at us, but throwing meaningful looks his attendant’s way. “Finish up there, you don’t want to delay the ladies.” The young man hurried off and was back momentarily with our change. He finished wrapping my purse.

As he handed it over, the attendant gave me an intent look. “Jorge Almonte,” he said, or something like that. “I put my card in your purse if there should ever be any need.”

The rain let up just as we came upon La Cumbre, the lonely mountain village that had grown up around one of Trujillo’s seldom-used mansions.

Too isolated, some people said. El Jefe’s two-story concrete house sat on top of the mountain above a cluster of little palm huts that seemed to be barely holding on to the cliff. We craned our necks every time we went by.

What did we think we’d see? A young girl brought here for a forced rendezvous? The old man himself walking around his grounds, beating the side of his shiny boots with a riding crop.

The iron gateway blazed its five stars above the gleaming T. As we passed, our young soldier passenger saluted, though no guards were in sight.

We drove by shabby palm huts. The one time we had stopped here to stretch our legs the whole little village had gathered, offering to sell us anything we might want to buy. “Things are bad,” the villagers complained, looking up towards the big house.

Rufino pulled over and rolled up the side flaps. A welcome breeze blew in, laden with the smells of damp vegetation. “Ladies,” Rufino asked us, before climbing back in, “if you’d like to stop?”

Patria was sure she did not want to stop. This was her first time, and the road was a little spooky until you got used to it.

Just as we were rounding the curve—on that stretch where the house shows the most from the road, I glanced up. “Why, look who’s there!” I said, pointing to the big white Mercedes that sat by the front door.

All three of us knew at the same instant what it meant. An ambush lay ahead! Why else was Pena at La Cumbre? We had seen him just this morning in Santiago when we picked up our permissions. Patria’s chatty friend had made no mention of being headed in our direction.

We could not turn around now. Were we being followed? We stuck our heads out the window to see what lay behind as well as ahead.

“I give myself to San Marco de León,” Patria intoned, repeating the prayer for desperate situations. I found myself mouthing the silly words.

Panic was rising up from my toes, through my guts, into my throat. The thunder in my chest exploded. Mate was already wheezing, searching through her purse for her medication. We sounded like a mobile sanatorium.

Rufino slowed. “Shall we stop at the three crosses?” Up ahead on a shoulder were three white crosses marking the casualties from a recent accident. Suddenly, it loomed in my head as the place for an ambush. The last place we should stop.

“Keep on going, Rufino ;‘ I said, and I took great swallows of the cool air that was blowing in on us.

To divert ourselves, Mate and I began moving the contents of our old purses into our new ones. The card of Jorge Almonte, Attendant, EL GALLO, found its way to my hand. The gold rooster logo crowed from the upper right-hand comer. I turned the card over. The words were written in big block letters in a hurried hand: “Avoid the pass.” My hand shook. I would not tell the others. It could only make things worse, and Mate’s asthma had just begun to calm down.

But in my own head I was working it all out: it was a movie scene that became suddenly, terrifyingly real. This soldier was a plant. How foolish we’d been, picking him up on this lonely country road.

I began chatting him up, trying to catch him in a lie. What time was he due at the fort and why had he hitched rather than caught a ride in an army truck? Finally, he turned around halfway in his seat. I could see that he was afraid to speak.

I’ll coax it out of him, I thought. “What is it? You can tell me.”

“You ask more questions than mi mujer when I get home,” he blurted out.

His color deepened at the rude suggestion that I could be like his wife.

Patria laughed and tapped my head with a gloved hand. “That coco fell right on your head.” I could see she, too, felt surer of him now.

The sun broke through the clouds, and shafts of light shone like blessings on the far valley. The arc of His covenant, I thought. I will not destroy my people. We had been silly, letting ourselves believe all those crazy rumors.

To entertain us, Mate began telling riddles she was sure we hadn’t heard.

We humored her. Then Rufino, who collected them, knowing how much Mate loved them, offered a new one to her. We began to descend towards the coast, the roadside growing more populous, the smell of the ocean in the air. The isolated little huts gave way to wooden houses with freshly painted shutters and zinc roofs advertising Ron Bermúdez on one side, Dios y Trujillo on the other.

Our soldier had been laughing loudly at the riddles he always guessed wrong. He had one of his own to contribute. It turned out to be much nastier than any of Mate‘s!

Rufino was indignant. “A Dio‘, are you forgetting there are ladies in the car?”

Patria leaned forward, patting a hand on each man’s shoulder. “Now, Rufino, every egg needs a little pepper.” We all laughed, glad for the release of the pent-up tension.

Mate crossed her legs, jiggling them up and down. “We’re going to have to stop soon unless you quit making me laugh.” She was famous for her tiny bladder. In prison, she’d had to practice holding it in since she didn’t like going out to the latrine with strange guards in the middle of the night.

“Everybody serious,” I ordered, “because we sure can’t stop here.”

We were at the outskirts of the city now. Brightly colored houses sat prettily in their kempt plots, side by side. The rain had washed the lawns, and the grasses and hedges shone emerald green. Everything was a fresh joy to see. Groups of children played in puddles on the street, scattering as the Jeep approached, so as not to be sprayed. An impulse seized me. I called out to them, “We’re here, safe and sound!”

They stopped their play and looked up. Their baffled little faces did not know what to make of us. But I kept waving until they waved back. I felt giddy, as if I’d been granted a reprieve from my worse fears. When Mate needed a piece of paper for her discarded Chiclet, I pulled out Jorge’s card.

Manolo was upset at his mother for letting us come alone. “She promised me she wouldn’t let you out of her sight.”

“But, my love,” I said, folding my hands over his, “reason it out. What could Doña Fefita do to protect me even if I were in danger?” I had a brief, ludicrous picture of the old, rather heavy woman banging a SIM calie over the head with her ubiquitous black purse.

Manolo pulled and pulled at his ear, a nervous habit he had developed in prison. It moved me to see him so nakedly affected by his long months of suffering. “A promise is a promise,” he concluded, still aggrieved. Oh dear, there would be words next time, and then Doña Fefita’s tears all the way home.

Manolo’s color had started to come back. This was definitely a better prison, brighter, cleaner than La Victoria. Every day, our friends Rudy and Pilar sent over a hot meal, and after they ate, the men were allowed to walk around in the prison yard for a half hour. Leandro, the engineer, joked that he and Manolo could have mashed at least a ton of sug arcane by now if they’d been rigged up with a harness like a team of oxen.

We sat around in the little yard where they usually brought us during our visits if the weather was good. Unaccountably, after the bad storm, the sun had come out in the late afternoon. It shone on the barracks, painted a pea- green, amoeba-shaped camouflage that looked almost playful; on the storybook towers with flags flying in a row; on the bars gleaming brightly, as if someone had taken the time to polish them. If you didn’t let yourself think what this place was, you could almost see it in a promising light.

Tentatively, Patria brought up the topic. “Have you been told anything about being moved back?”

Leandro and Manolo looked at each other. A worried look passed between them. “Did Pedrito hear something?”

“No, no, nothing like that,” Patria soothed them. And then she looked to me to bring up what the young soldier had reported in the car, that two “politicals” would be going back to La Victoria in a few weeks.

But I did not want to worry them. Instead I began to describe the perfect little house we’d seen earlier. Patria and Mate joined in. What we didn’t tell the men was that we had not rented the house, after all. If they were going to be moved back to La Victoria, there was no use. The big white Mercedes parked at the door of La Cumbre crossed my mind. I leaned forward, as if to leave its image physically at the back of my mind.

We heard the clanging of doors in the distance. Footsteps approached, there were shouted greetings, the click and slap of gun salutes. The guard was changing.

Patria opened her purse and withdrew her scarf. “Ladies, the shades of night begin to fall, the wayfarer hurries home …”

“Nice poetry.” I laughed to lighten the difficult moment. I had such a hard time saying goodbye.

“You’re not going back tonight?” Manolo looked shocked at the idea.

“It’s too late to start out. I want you to stay with Rudy and Pilar and head back tomorrow.”

“I touched his raspy cheek with the back of my hand. He shut his eyes, giving himself to my touch. ”You mustn’t worry so. Look how clear that sky is. Tomorrow we’ll probably have another bad storm. We’re better off going home this evening.“

We all looked up at the deepening, golden sky. The few low-lying clouds were moving quickly across it—as if heading home themselves before it got too dark.

I didn’t tell him the real reason why I didn’t want to stay with his friends.

Pilar had confided in me as we drove around looking at houses that Rudy’s

business was about to collapse. She did not have to say it, but I guessed why. We had to put more distance between us, for their sake.

Manolo held my head in both his hands. I wanted to lose myself in his sad dark eyes. “Please, mi amor. There are too many rumors around.”

I reasoned with him. “If you gave me a peso for every premonition, dream, admonition we’ve been told this month, we’d be able to—”

“Buy ourselves another set of purses.” Mate held hers up and nodded for me to hold up mine.

Then, there was the call, “Time!” The guards closed in, their flat, empty faces showing us no consideration. “Time!”

We stood, said our hurried goodbyes, our whispered prayers and endearments. Remember … Don’t forget … Dios te bendiga, mi amor. A final embrace before they were led away. The light was falling quickly. I turned for a last look but they had already disappeared into the barracks at the end of the yard.

We stopped at the little restaurant-gas pump on the way out of town. The umbrellas had all been taken down in preparation for night, and only the little tables remained. Since Mate and Patria were thirsty and wanted a refreshment, I went and made the call. The line was busy.

I paced back and forth in front of the phone the way one does to remind someone ahead that others are waiting. But neither Mamá nor Dedé could know that I was waiting for them to get off the line.

“Still busy,” I came back and told my sisters.

Mate picked up her new purse and mine from the extra chair. “Sit with us, come on.” But I couldn’t see how I could sit. I guess it was getting to me, listening to everyone’s worries.

“Give it another five minutes,” Patria suggested. It seemed reasonable enough. In five minutes whoever was on would be off the line. If not, it was

a sure sign that one of the children had left the phone off the hook and who knew when Tono or Fela would discover it.

Rufino leaned against the back of the Jeep, his arms crossed. Every so often, he’d look up at the sky—checking the time.

“I think maybe I will have a beer,” I said at last.

“iEpa!” Mate said. She was drinking her lemonade through a straw, daintily like a girl, trying to make the sweet pleasure last. We would be stopping at least once more on the road. I could see that.

“Rufino, can I get you one?” He looked away, a sign that indeed he would like a cold beer but was too shy to say so. Off I went to the bar for our two Presidentes. I tried the number again while the obliging proprietor dug up his two coldest ones from the bottom of the deep freeze.

“Still busy,” I told our little table when I got back.

“Minerva!” Patria shook her head. “That wasn’t five minutes.”

The afternoon was deepening towards evening. I felt the cooler air of night blowing off the mountain. We had not brought our shawls. I imagined Mama just now seeing them, draped brightly on the backs of chairs, and going to the window once again to watch for car lights.

Undoubtedly, she would pass the phone. She would see it was off the hook. She would heave a sigh and replace it in its cradle. I went back to try one more time.

“I give up,” I said when I came back. “I think we should just go.”

Patria looked up at the mountain. Behind it was another one and another one, but then we would be home. “I feel a little uneasy. I mean that road is so—deserted.”

“It’s always that way,” I informed her. The veteran mountain-pass traveler.

Mate finished the last of her drink and sucked the sugar through the straw, making a rude sound. “I promised Jacqui I’d tuck her in tonight.” Her voice had a whiny edge. Mate had not been separated from her baby overnight since we’d come home from prison.

“What do you say, Rufino?” I asked him.

“We can make it to La Cumbre before dark, for sure. From there, it’s all downhill. But it’s up to you,” he added, not wanting to express a preference.

Surely, his own bed with Delisa curled beside him was better than a little cot in the tiny servant’s room at the back of Rudy and Pilar’s yard. He had a baby, too. It struck me I had never asked him how old the child was, boy or girl.

“I say we go,” I said, but I still read hesitancy in Patria’s face.

Just then, a Public Works truck pulled into the station. Three men got out.

One veered off behind the building to the smelly toilet we had been forced to use once and swore never again. The other two came up to the counter, shaking their legs and pulling at their crotches, the way men getting out of cars do. They greeted the proprietor warmly, giving him half-arm abrazos over the counter. “How are you, compadre? No, no, we can’t stay. Pack us up a dozen of those pork fries over there—in fact, hand us a couple to eat right now.”

The proprietor talked with the men as he filled their order. “Where you headed at this hour, boys?”

The driver had taken a large bite of the fried rind in his hand. “Truck needs to be in Tamboril by dark.” He spoke with his mouth full, licking his greasy fingers when he was done and then tweezing a handkerchief out of his back pocket to wipe himself. “Tito! Where is that Tito?” He turned around and scanned the tables, his eye falling on us. We smiled, and he took his cap off and held it to his heart. The flirt. Rufino straightened up protectively from his post next to the car.

When Tito came running from behind the pumps, his buddies were already inside the truck, gunning the motor. “Can’t a man shit in peace?” he called out, but the truck was inching forward, and he had to execute a tricky mount on the passenger’s running board. I was sure they had performed the maneuver before for a lady or two. They honked as they pulled out into the road.

We looked at each other. Their lightheartedness made us all feel safer somehow. We’d be following that truck all the way to the other side of the

mountains. Suddenly, the road was not so lonesome.

“What do you say?” I said, standing up. “Shall I try one more time?” I looked towards the phone.

Patria closed her purse with a decisive snap. “Let’s just go.”

We moved quickly now towards the Jeep, hurrying as if we had to catch up with that truck. I don’t know quite how to say this, but it was as if we were girls again, walking through the dark part of the yard, a little afraid, a little excited by our fears, anticipating the lighted house just around the bend—

That’s the way I felt as we started up the first mountain.

Epilogue

Dedé

1994

Later they would come by the old house in Ojo de Agua and insist on seeing me. Sometimes, for a rest, I’d go spend a couple of weeks with Mamá in Conuco. I would use the excuse that the monument was being built, and the noise and dust and activity bothered me. But it was really that I could bear neither to receive them nor turn them away.

They would come with their stories of that afternoon—the little soldier with the bad teeth, cracking his knuckles, who had ridden in the car with them over the mountain; the bowing attendant from El Gallo who had sold them some purses and tried to warn them not to go; the big-shouldered truck driver with the husky voice who had witnessed the ambush on the road. They all wanted to give me something of the girls’ last moments.

Each visitor would break my heart all over again, but I would sit on this very rocker and listen for as long as they had something to say.

It was the least I could do, being the one saved.

And as they spoke, I was composing in my head how that last afternoon went.

It seems they left town after four-thirty, since the truck that preceded them up the mountain clocked out of the local Public Works building at four thirty-five. They had stopped at a little establishment by the side of the

road. They were worrying about something, the proprietor said, he didn’t know what. The tall one kept pacing back and forth to the phone and talking a lot.

The proprietor had had too much to drink when he told me this. He sat in that chair, his wife dabbing at her eyes each time her husband said something. He told me what each of them had ordered. He said I might want to know this. He said at the last minute the cute one with the braids decided on ten cents’ worth of Chiclets, cinnamon, yellow, green. He dug around in the jar but he couldn’t find any cinnamon ones. He will never forgive himself that he couldn’t find any cinnamon ones. His wife wept for the little things that could have made the girls’ last minutes happier. Their sentimentality was excessive, but I listened, and thanked them for coming.

It seems that at first the Jeep was following the truck up the mountain. Then as the truck slowed for the grade, the Jeep passed and sped away, around some curves, out of sight. Then it seems that the truck came upon the ambush. A blue-and-white Austin had blocked part of the road; the Jeep had been forced to a stop; the women were being led away peaceably, so the truck driver said, peaceably to the car. He had to brake so as not to run into them, and that’s when one of the women—I think it must have been Patria, “the short, plump one”—broke from the captors and ran towards the truck.

She clung to the door, yelling, “Tell the Mirabal family in Salcedo that the calies are going to kill us!” Right behind her came one of the men, who tore her hand off the door and dragged her away to the car.

It seems that the minute the truck driver heard the word calie, he shut the door he had started opening. Following the commanding wave of one of the men, he inched his way past. I felt like asking him, “Why didn’t you stop and help them?” But of course, I didn’t. Still, he saw the question in my eyes and he bowed his head.

Over a year after Trujillo was gone, it all came out at the trial of the murderers. But even then, there were several versions. Each one of the five murderers saying the others had done most of the murdering. One of them saying they hadn’t done any murdering at all. Just taken the girls to the mansion in La Cumbre where El Jefe had finished them off.

The trial was on TV all day long for almost a month.

Three of the murderers did finally admit to killing one each of the Mirabal sisters. Another one killed Rufino, the driver. The fifth stood on the side of the road to warn the others if someone was coming. At first, they all tried to say they were that one, the one with the cleanest hands.

I didn’t want to hear how they did it. I saw the marks on Minerva’s throat; fingerprints sure as day on Mate’s pale neck. They also clubbed them, I could see that when I went to cut her hair. They killed them good and dead. But I do not believe they violated my sisters, no. I checked as best I could. I think it is safe to say they acted like gentlemen murderers in that way.

After they were done, they put the dead girls in the back of the Jeep, Rufino in front. Past a hairpin curve near where there were three crosses, they pushed the car over the edge. It was seven-thirty The way I know is one of my visitors, Mateo Núnez, had just begun listening to the Sacred Rosary on his little radio when he heard the terrible crash.

He learned about the trial of the murderers on that same radio. He walked from his remote mountain shack with his shoes in a paper sack so as not to wear them out. It must have taken him days. He got a lift or two, here and there, sometimes going the wrong way. He hadn’t traveled much off that mountain. I saw him out the window when he stopped and put on his shoes to show up proper at my door. He gave me the exact hour and made the thundering noise of the tumbling Jeep he graphed with his arcing hand.

Then he turned around and headed back to his mountain.

He came all that way just to tell me that.

The men got thirty years or twenty years, on paper. I couldn’t keep straight why some of the murderers got less than the others. Likely the one on the road got the twenty years. Maybe another one was sorry in court. I don’t know But their sentences didn’t amount to much, anyway. All of them were set free during our spell of revolutions. When we had them regularly, as if to prove we could kill each other even without a dictator to tell us to.

After the men were sentenced, they gave interviews that were on the news all the time. What did the murderers of the Mirabal sisters think of this and that? Or so I heard. We didn’t own a TV, and the one at Mamá’s we turned on only for the children’s cartoons. I‘didn’t want them to grow up with hate, their eyes fixed on the past. Never once have the names of the murderers crossed my lips. I wanted the children to have what their mothers would have wanted for them, the possibility of happiness.

Once in a while, Jaimito brought me a newspaper so I could see all the great doings in the country. But I’d roll it up tight as I could get it and whack at the house flies. I missed some big things that way. The day Trujillo was assassinated by a group of seven men, some of them his old buddies. The day Manolo and Leandro were released, Pedrito having already been freed. The day the rest of the Trujillo family fled the country.

The day elections were announced, our first free ones in thirty-one years.

“Don’t you want to know all about it?” Jaimito would ask, grinning, trying to get me excited. Or more likely, hopeful. I’d smile, grateful for his caring. “Why? When I can hear it all from you, my dear?”

Not that I was really listening as he went on and on, recounting what was in the papers. I pretended to, nodding and smiling from my chair. I didn’t want to hurt his feelings. After all, I listened to everyone else.

But the thing was, I just couldn’t take one more story.

In her mother’s old room, I hear Minou, getting ready for bed. She keeps a steady patter through the open window, catching me up on her life since we last talked. The new line of play clothes she designed for her store in the capital; the course she is teaching at the university on poetry and politics;

Jacqueline’s beautiful little baby and the remodeling of her penthouse; Manolito, busy with his agricultural projects—all of them smart young men and women making good money. They aren’t like us, I think. They knew almost from the start they had to take on the world.

“Am I boring you, Mamá Dedé?”

“Not at all!” I say, rocking in pleasing rhythm to the sound of her voice.

The little news, that’s what I like, I tell them. Bring me the little news.

Sometimes they came to tell me just how crazy I was. To say, “Ay, Dedé, you should have seen yourself that day!”

The night before I hadn’t slept at all. Jaime David was sick and kept waking up, feverish, needing drinks of water. But it wasn’t him keeping me up. Every time he cried out I was already awake. I finally came out here and waited for dawn, rocking and rocking like I was bringing the day on.

Worrying about my boy, I thought.

And then, a soft shimmering spread across the sky. I listened to the chair rockers clacking on the tiles, the isolated cock crowing, and far off, the sound of hoof beats, getting closer, closer. I ran all the way around the galería to the front. Sure enough, here was Mamá’s yardboy galloping on the mule, his legs hanging almost to the ground. Funny, the thing that you remember as most shocking. Not a messenger showing up at that eerie time of early dawn, the dew still thick on the grass. No. What shocked me most was that anybody had gotten our impossibly stubborn mule to gallop.

The boy didn’t even dismount. He just called out, “Doña Dedé, your mother, she wants you to come right away.”

I didn’t even ask him why. Did I already guess? I rushed back into the house, into our bedroom, threw open the closet, yanked my black dress off its hanger, ripping the right sleeve, waking Jaimito with my piteous crying.

When Jaimito and I pulled into the drive, there was Mamá and all the kids running out of the house. I didn’t think the girls, right off. I thought, there’s a fire, and I started counting to make sure everybody was out.

The babies were all crying like they had gotten shots. And here comes Minou tearing away from the others towards the truck so Jaimito had to screech to a stop.

“Lord preserve us, what is going on?” I ran to them with my arms open.

But they hung back, stunned, probably at the horror on my face, for I had

noticed something odd.

“Where are they!?” I screamed.

And then, Mamá says to me, she says, “Ay, Dedé, tell me it isn’t true, ay, tell me it isn’t true.”

And before I could even think what she was talking about, I said, “It isn’t true, Mamá, it isn’t true.”

There was a telegram that had been delivered first thing that morning. Once she’d had it read to her, Mama could never find it again. But she knew what

it said.

There has been a car accident.

Please come to Jose Maria Cabral Hospital in Santiago.

And my heart in my rib cage was a bird that suddenly began to sing.

Hope! I imagined broken legs strung up, arms in casts, lots of bandages. I rearranged the house where I was going to put each one while they were convalescing. We’d clear the living room and roll them in there for meals.

While Jaimito was drinking the cup of coffee Tono had made him—I hadn’t wanted to wait at home while the slow-witted Tinita got the fire going—Mamá and I were rushing around, packing a bag to take to the hospital. They would need nightgowns, toothbrushes, towels, but I put in crazy things in my terrified rush, Mate’s favorite earrings, the Vicks jar, a brassiere for each one.

And then we hear a car coming down the drive. At our spying jalousie— as we called that front window—I recognize the man who delivers the

telegrams. I say to Mamá, wait here, let me go see what he wants. I walk quickly up the drive to stop that man from coming any closer to the house, now that we had finally gotten the children calmed down.

“We’ve been calling. We couldn’t get through. The phone, it’s off the hook or something.” He is delaying, I can see that. Finally he hands me the little envelope with the window, and then he gives me his back because a man can’t be seen crying.

I tear it open, I pull out the yellow sheet, I read each word.

I walk back so slowly to the house I don’t know how I ever get there.

Mama comes to the door, and I say, Mamá, there is no need for the bag.

At first the guards posted outside the morgue did not want to let me in. I was not the closest living relative, they said. I said to the guards, “I’m going in there, even if I have to be the latest dead relative. Kill me, too, if you want. I don’t care.”

The guards stepped back. “Ay, Dedé,” the friends will say, “you should have seen yourself.”

I cannot remember half the things I cried out when I saw them. Rufino and Minerva were on gumeys, Patria and Mate on mats on the floor. I was furious that they didn’t all have gumeys, as if it should matter to them. I remember Jaimito trying to hush me, one of the doctors coming in with a sedative and a glass of water. I remember asking the men to leave while I washed up my girls, and dressed them. A nurse helped me, crying, too. She brought me some little scissors to cut off Mate’s braid. I cannot imagine why in a place with so many sharp instruments for cutting bones and thick tissues, that woman brought me such teeny nail scissors. Maybe she was afraid what I would do with something sharper.

Then some friends who had heard the news appeared with four boxes, plain simple pine without even a latch. The tops were just nailed down.

Later, Don Gustavo at the funeral parlor wanted us to switch them into something fancy. For the girls, anyhow. Pine was appropriate enough for a chauffeur.

I remembered Papá’s prediction, Dedé will bury us all in silk and pearls.

But I said no. They all died the same, let them all be buried the same.

We stacked the four boxes in the back of the pickup.

We drove them home through the towns slowly. I didn’t want to come inside the cab with Jaimito. I stayed out back with my sisters, and Rufino, standing proud beside them, holding on to the coffins whenever we hit a bump.

People came out of their houses. They had already heard the story we were to pretend to believe. The Jeep had gone off the cliff on a bad turn.

But their faces knew the truth. Many of the men took off their hats, the women made the sign of the cross. They stood at the very edge of the road, and when the truck went by, they threw flowers into the bed. By the time we reached Conuco, you couldn’t see the boxes for the wilting blossoms blanketing them.

When we got to the SIM post at the first little town, I cried out, “Assassins! Assassins!”

Jaimito gunned the motor to drown out my cries. When I did it again at the next town, he pulled over and came to the back of the pickup. He made me sit down on one of the boxes. “Dedé, mujer, what is it you want—to get yourself killed, too?”

I nodded. I said, “I want to be with them.”

He said—I remember it so clearly—he said, “This is your martyrdom, Dede, to be alive without them.”

“What are you thinking, Mama Dedé?” Minou has come to the window.

With her arms folded on the sill, she looks like a picture.

I smile at her and say, “Look at that moon.” It is not a remarkable moon, waning, hazy in the cloudy night. But as far as I’m concerned, a moon is a

moon, and they all bear remarking. Like babies, even homely ones, each a blessing, each one born with—as Mama used to say—its loaf of bread under its arm.

“Tell me about Camila,” I ask her. “Has she finished growing that new tooth?”

With first-time-mother exactitude Minou tells me everything, down to how her little girl feeds, sleeps, plays, poops.

Later the husbands told me their stories of that last afternoon. How they tried to convince the girls not to go. How Minerva refused to stay over with friends until the next morning. “It was the one argument she should have lost,” Manolo said. He would stand by the porch rail there for a long time, in those dark glasses he was always wearing afterwards. And I would leave him to his grief.

This was after he got out. After he was famous and riding around with bodyguards in that white Thunderbird some admirer had given him. Most likely a woman. Our Fidel, our Fidel, everyone said. He refused to run for president for those first elections. He was no politician, he said. But everywhere he went, Manolo drew adoring crowds.

He and Leandro were transferred back to the capital the Monday following the murder. No explanation. At La Victoria, they rejoined Pedrito, the three of them alone in one cell. They were extremely nervous, waiting for Thursday visiting hours to find out what was going on. “You had no idea?” I asked Manolo once. He turned around right there, with that oleander framing him. Minerva had planted it years back when she was cooped up here, wanting to get out and live the bigger version of her life.

He took off those glasses, and it seemed to me that for the first time I saw the depth of his grief.

“I probably knew, but in prison, you can’t let yourself know what you know.” His hands clenched the porch rail there. I could see he was wearing his class ring again, the one that had been on Minerva’s hand.

Manolo tells how that Thursday they were taken out of their cell and marched down the hall. For a brief moment they were hopeful that the girls were all right after all. But instead of the visitors’ room, they were led downstairs to the officers’ lounge. Johnny Abbes and Cándido Torres and other top SIM cronies were waiting, already quite drunk. This was going to be a special treat, by invitation only, a torture session of an unusual nature, giving the men the news.

I didn’t want to listen anymore. But I made myself listen—it was as if Manolo had to say it and I had to hear it—so that it could be human, so that we could begin to forgive it.

There are pictures of me at that time where even I can’t pick myself out.

Thin like my little finger. A twin of my skinny Noris. My hair cropped short like Minerva’s was that last year, held back by bobby pins. Some baby or other in my arms, another one tugging at my dress. And you never see me looking at the camera. Always I am looking away.

But slowly—how does it happen?—I came back from the dead. In a photo I have of the day our new president came to visit the monument, I’m standing in front of the house, all made up, my hair in a bouffant style.

Jacqueline is in my arms, already four years old. Both of us are waving little flags.

Afterwards, the president dropped in for a visit. He sat right there in Papa’s old rocker, drinking a frozen limonada, telling me his story. He was going to do all sorts of things, he told me. He was going to get rid of the old generals with their hands still dirty with Mirabal blood. All those properties they had stolen he was going to distribute among the poor. He was going to make us a nation proud of ourselves, not run by the Yanqui imperialists.

Every time he made one of these promises, he’d look at me as if he needed me to approve what he was doing. Or really, not me, but my sisters whose pictures hung on the wall behind me. Those photos had become icons, emblazoned on posters—already collectors’ pieces. Bring back the butterflies!

At the end, as he was leaving, the president recited a poem he’d composed on the ride up from the capital. It was something patriotic about how when you die for your country, you do not die in vain. He was a poet president, and from time to time Manolo would say, “Ay, if Minerva had lived to see this.” And I started to think, maybe it was for something that the girls had died.

Then it was like a manageable grief inside me. Something I could bear because I could make sense of it. Like when the doctor explained how if one breast came off, the rest of me had a better chance. Immediately, I began to live without it, even before it was gone.

I set aside my grief and began hoping and planning.

When it all came down a second time, I shut the door. I did not receive any more visitors. Anyone had a story, go sell it to Vanidades, go on the Talk to Felix Show. Tell them how you felt about the coup, the president thrown out before the year was over, the rebels up in the mountains, the civil war, the landing of the marines.

I overheard one of the talk shows on the radio Tinita kept turned on in the outdoor kitchen all the time. Somebody analyzing the situation. He said something that made me stop and listen.

“Dictatorships,” he was saying, “are pantheistic. The dictator manages to plant a little piece of himself in every one of us.”

Ah, I thought, touching the place above my heart where I did not yet know the cells were multiplying like crazy. So this is what is happening to us.

Manolo’s voice sounds blurry on the memorial tape the radio station sent me, In memory of our great hero. When you die for your country, you do not die in vain.

It is his last broadcast from a hidden spot in the mountains. “Fellow Dominicans!” he declaims in a grainy voice. “We must not let another dictatorship rule us!” Then something else lost in static. Finally, “Rise up, take to the streets! Join my comrades and me in the mountains! When you die for your country, you do not die in vain!”

But no one joined them. After forty days of bombing, they accepted the broadcast amnesty. They came down from the mountains with their hands up, and the generals gunned them down, every one.

I was the one who received the seashell Manolo sent Minou on his last day. In its smooth bowl he had etched with a penknife, For my little Minou, at the end of a great adventure, then the date he was murdered, December 21, 1963. I was furious at his last message. What did he mean, a great adventure. A disgrace was more like it.

I didn’t give it to her. In fact, for a while, I kept his death a secret from her. When she’d ask, I’d tell her, “Sí, si, Papi is up in the mountains fighting for a better world.” And then, you see, after about a year or so of that story it was an easy next step for him to be up in heaven with her Mami and her Tía Patria and her Tía Mate living in a better world.

She looked at me when I told her this—she must have been eight by then —and her little face went very serious. “Mamá Dedé,” she asked, ”is Papi dead?“

I gave her the shell so she could read his goodbye for herself.

“That was a funny woman,” Minou is saying. “At first I thought you were friends or something. Where did you pick her up, Mama Dedé?”

“Me? Pick her up! You seem to forget, mi amor, that the museum is just five minutes away and everyone shows up there wanting to hear the story, firsthand.” I am rocking harder as I explain, getting angrier. Everyone feels they can impose. The Belgian movie maker who had me pose with the girls’ photos in my hands; the Chilean woman writing a book about women and politics; the schoolchildren who want me to hold up the braid and tell them why I cut it off in the first place.

“But, Mama Dedé,” Minou says. She is sitting on the sill now, peering out from her lighted room into the galería whose lights I’ve turned off against the mosquitoes. “Why don’t you just refuse. We’ll put the story on cassette, a hundred and fifty pesos, with a signed glossy photograph thrown in for free.”

“Why, Minou, the idea!” To make our tragedy—because it is our tragedy, really, the whole country‘s—to make it into a money-making enterprise.

But I see she is laughing, enjoying the deliciously sacrilegious thought. I laugh, too. “The day I get tired of doing it, I suppose I’ll stop.”

My rocking eases, calmed. Of course, I think, I can always stop.

“When will that be, Mamá Dedé, when will you have given enough?”

When did it turn, I wonder, from my being the one who listened to the stories people brought to being the one whom people came to for the story of the Mirabal sisters?

When, in other words, did I become the oracle?

My girlfriend Olga and I will sometimes get together for supper at a restaurant. We can do this for ourselves, we tell each other, like we don’t half believe it. Two divorced mujeronas trying to catch up with what our children call the modern times. With her I can talk over these things. I’ve asked her, what does she think.

“I’ll tell you what I think,” Olga says. We are at El Almirante, where— we have decided—the waiters must be retired functionaries from the old Trujillo days. They are so self-important and ceremonious. But they do let two women dine alone in peace.

“I think you deserve your very own life,” she is saying, waving my protest away. “Let me finish. You’re still living in the past, Dedé. You’re in the same old house, surrounded by the same old things, in the same little village, with all the people who have known you since you were this big.”

She goes over all these things that supposedly keep me from living my own life. And I am thinking, Why, I wouldn’t give them up for the world.

I’d rather be dead.

“It’s still 1960 for you,” she concludes. “But this is 1994, Dedé, 1994!”

“You’re wrong,” I tell her. “I’m not stuck in the past, I’ve just brought it with me into the present. And the problem is not enough of us have done that. What is that thing the gringos say, if you don’t study your history, you are going to repeat it?”

Olga waves the theory away. “The gringos say too many things.”

“And many of them true,” I tell her. “Many of them.” Minou has accused me of being pro-Yanqui. And I tell her, “I am pro whoever is right at any moment in time.”

Olga sighs. I already know. Politics do not interest her.

I change the subject back to what the subject was. “Besides, that’s not what I asked you. We were talking about when I became the oracle instead of the listener.”

“Hmm,” she says. “I’m thinking, I’m thinking.”

So I tell her what I think.

“After the fighting was over and we were a broken people”—she shakes her head sadly at this portrait of our recent times—“that’s when I opened my doors, and instead of listening, I started talking. We had lost hope, and we needed a story to understand what had happened to us.”

Olga sits back, her face attentive, as if she were listening to someone preach something she believes. “That’s really good, Dedé,” she says when I finish. ”You should save that for November when you have to give that speech.“

I hear Minou dialing, putting in a call to Doroteo, their goodnight tête-à- tête, catching up on all the little news of their separated hours. If I go in now, she’ll feel she has to cut it short and talk to her Mamá Dedé instead.

And so I come stand by the porch rail, and the minute I do, of course, I can’t help thinking of Manolo and of Minerva before him. We had this game called Dark Passages when we were children. We would dare each other to walk down into the dark garden at night. I only got past this rail once or twice. But Minerva, she’d take off, so that we’d have to call and

call, pleading for her to come back. I remember, though, how she would stand right here for a moment, squaring her shoulders, steeling herself. I could see it wasn’t so easy for her either.

And when she was older, every time she got upset, she would stand at this same rail. She’d look out into the garden as if that dark tangle of vegetation were the new life or question before her.

Absently, my hand travels to my foam breast and presses gently, worrying an absence there.

“Mi amor,” I hear Minou say in the background, and I feel goose bumps all up and down my arms. She sounds so much like her mother. “How’s our darling? Did you take her to Helados Bon?”

I walk off the porch onto the grass, so as not to overhear her conversation, or so I tell myself. For a moment I want to disappear. My legs brushing fragrances off the vague bushes, the dark growing deeper as I walk away from the lights of the house.

The losses. I can count them up like the list the coroner gave us, taped to the box of things that had been found on their persons or retrieved from the wreck. The silliest things, but they gave me some comfort. I would say them like a catechism, like the girls used to tease and recite “the

commandments” of their house arrest.

One pink powder puff.

One pair of red high-heeled shoes.

The two-inch heel from a cream-colored shoe.

Jaimito went away for a time to New York. Our harvests had failed again, and it looked as if we were going to lose our lands if we didn’t get some cash quick. So he got work in a factoria, and every month, he sent home money. I am ashamed after what came to pass to say so. But it was gringo dollars that saved our farm from going under.

And when he came back, he was a different man. Rather, he was more who he was. I had become more who I was, too, locked up, as I said, with Mamá and the children my only company. And so, though we lived under

the same roof until after Mama died, to spare her another sadness, we had

already started on our separate lives.

One screwdriver.

One brown leather purse.

One red patent leather purse with straps missing.

One pair of yellow nylon underwear.

One pocket mirror.

Four lottery tickets.

We scattered as a family, the men, and later the children, going their separate ways.

First, Manolo, dead within three years of Minerva.

Then Pedrito. He had gotten his lands back, but prison and his losses had changed him. He was restless, couldn’t settle down to the old life. He remarried a young girl, and the new woman turned him around, or so Mamá thought. He came by a lot less and then hardly at all. How all of that, beginning with the young girl, would have hurt poor Patria.

And Leandro. While Manolo was alive, Leandro was by his side, day and night. But when Manolo took off to the mountains, Leandro stayed home.

Maybe he sensed a trap, maybe Manolo had become too radical for Leandro, I don’t know. After Manolo died, Leandro got out of politics.

Became a big builder in the capital. Sometimes when we’re driving through the capital, Jacqueline points out one impressive building or another and says, “Papá built that.” She is less ready to talk about the second wife, the new, engrossing family, stepbrothers and sisters the age of her own little

one.

One receipt from El Gallo.

One missal held together with a rubber band.

One man’s wallet, 56 centavos in the pocket.

Seven rings, three plain gold bands, one gold with a small diamond stone, one gold with an opal and four pearls, one man’s ring with garnet and eagle

insignia, one silver initial ring.

One scapular of our Lady of Sorrows.

One Saint Christopher’s medal.

Mama hung on twenty years. Every day I wasn’t staying over, I visited her first thing in the morning and always with an orchid from my garden for the girls. We raised the children between us. Minou and Manolito and

Raulito, she kept. Jacqueline and Nelson and Noris were with me. Don’t ask me why we divided them that way. We didn’t really. They would wander from house to house, they had their seasons, but I’m talking about where they most often slept.

What a time Mama had with those teenage granddaughters. She wanted them locked up like nuns in a convent, she was always so afraid. And Minou certainly kept her—and me—in worries. She took off, a young sixteen-year-old, by herself to study in Canada. Then it was Cuba for several years. ¡Ay, Dios! We pinned enough Virgencitas and azabaches and hung enough scapulars around that girl’s neck to charm away the men who were always wanting to get their hands on that young beauty.

I remember Minou telling me about the first time she and Doroteo “got involved”—what she called it. I imagined, of course, the bedside scene behind the curtain of that euphemism. He stood with his hands under his arms as if he were not going to give in to her charms. Finally, she said, “Doroteo, what’s wrong?” And Doroteo said, “I feel like I’d be desecrating the flag.”

He had a point there. Imagine, the daughter of two national heroes. All I said to Minou was “I like that young man.”

But not Mama. “Be smart like your mother,” she kept saying. “Study and marry when you’re older.” And all I could think of was the hard time Mama had given Minerva when she had done just that!

Poor Mamá, living to see the end of so many things, including her own ideas. Twenty years, like I said, she hung on. She was waiting until her granddaughters were past the dangerous stretch of their teen years before she left them to fend for themselves.

And then fourteen years ago this last January, I came into her bedroom one morning, and she was lying with her hands at her waist, holding her rosary, quiet, as if she were praying. I checked to make sure she was gone.

It was strange how this did not seem a real death, so unlike the others, quiet, without rage or violence.

I put the orchid I had brought the girls in her hands. I knew that, unless my destiny was truly accursed and I survived my children, this was the last big loss I would have to suffer. There was no one between me and the dark passage ahead—I was next.

The complete list of losses. There they are.

And it helps, I’ve found, if I can count them off, so to speak. And sometimes when I’m doing that, I think, Maybe these aren’t losses. Maybe that’s a wrong way to think of them. The men, the children, me. We went our own ways, we became ourselves. Just that. And maybe that is what it means to be a free people, and I should be glad?

Not long ago, I met Lio at a reception in honor of the girls. Despite what Minou thinks, I don’t like these things. But I always make myself go.

Only if I know he will be there, I won’t go. I mean our current president who was the puppet president the day the girls were killed. “Ay, Dedé,” acquaintances will sometimes try to convince me. “Put that behind you.

He’s an old, blind man now.”

“He was blind when he could see,” I’ll snap. Oh, but my blood bums just thinking of shaking that spotted hand.

But most things I go to. “For the girls,” I always tell myself.

Sometimes I allow myself a shot of rum before climbing into the car, not enough to scent the slightest scandal, just a little thunder in the heart.

People will be asking things, well meaning but nevertheless poking their fingers where it still hurts. People who kept their mouths shut when a little peep from everyone would have been a chorus the world couldn’t have ignored. People who once were friends of the devil. Everyone got amnesty by telling on everyone else until we were all one big rotten family of

cowards.

So I allow myself my shot of rum.

At these things, I always try to position myself near the door so I can leave early. And there I was about to slip away when an older man approached me. On his arm was a handsome woman with an open, friendly face. This old fool is no fool, I’m thinking. He has got himself his young nurse wife for his old age.

I put out my hand, just a reception line habit, I guess. And this man reaches out both hands and clasps mine. “Dedé, caramba, don’t you know

who I am?” He holds on tight, and the young woman is beaming beside him. I look again.

“iDios santo, Lío!” And suddenly, I have to sit down.

The wife gets us both drinks and leaves us alone. We catch up, back and forth, my children, his children; the insurance business, his practice in the capital; the old house I still live in, his new house near the old presidential palace. Slowly, we are working our way towards that treacherous past, the horrible crime, the waste of young lives, the throbbing heart of the wound.

“Ay, Lío,” I say, when we get to that part.

And bless his heart, he takes my hands and says, “The nightmare is over, Dedé. Look at what the girls have done.” He gestures expansively.

He means the free elections, bad presidents now put in power properly, not by army tanks. He means our country beginning to prosper, Free Zones going up everywhere, the coast a clutter of clubs and resorts. We are now the playground of the Caribbean, who were once its killing fields. The

cemetery is beginning to flower.

“Ay, Lío,” I say it again.

I follow his gaze around the room. Most of the guests here are young.

The boy-businessmen with computerized watches and walkie-talkies in their wives’ purses to summon the chauffeur from the car; their glamorous young wives with degrees they do not need; the scent of perfume; the tinkle of keys to the things they own.

“Oh yes,” I hear one of the women say “we spent a revolution there.”

I can see them glancing at us, the two old ones, how sweet they look under that painting of Bido. To them we are characters in a sad story about a past that is over.

All the way home, I am trembling, I am not sure why.

It comes to me slowly as I head north through the dark countryside-the only lights are up in the mountains where the prosperous young are building their getaway houses, and of course, in the sky, all the splurged wattage of the stars. Lío is right. The nightmare is over; we are free at last. But the thing that is making me tremble, that I do not want to say out loud-and I’ll say it once only and it’s done.

Was it for this, the sacrifice of the butterflies?

“Mamá Dedé! Where are you?” Minou must be off the phone. Her voice has that exasperated edge our children get when we dare wander from their lives. Why aren’t you where I left you? “Mamá Dedé!”

I stop in the dark depths of the garden as if I’ve been caught about to do something wrong. I turn around. I see the house as I saw it once or twice as a child: the roof with its fairytale peak, the verandah running along three sides, the windows lighted up, glowing with lived life, a place of abundance, a magic place of memory and desire. And quickly I head back, a moth attracted to that marvelous light.

I tuck her in bed and turn off her light and stay a while and talk in the dark.

She tells me all the news of what Camila did today. Of Doroteo’s businesses, of their plans to build a house up north in those beautiful mountains.

I am glad it is dark, so she cannot see my face when she says this. Up north in those beautiful mountains where both your mother and father were murdered!

But all this is a sign of my success, isn’t it? She’s not haunted and full of hate. She claims it, this beautiful country with its beautiful mountains and splendid beaches—all the copy we read in the tourist brochures.

We make our plans for tomorrow. We’ll go on a little outing to Santiago where I’ll help her pick up some fabrics at El Gallo. They’re having a big sale before they close the old doors and open under new management. A chain of El Gallos is going up all over the island with attendants in rooster- red uniforms and registers that announce how much you are spending. Then we’ll go to the museum where Minou can get some cuttings from Tono for the atrium in her apartment. Maybe Jaime David can have lunch with us.

The big important senator from Salcedo better have time for her, Minou warns me.

Fela’s name comes up. “Mamá Dedé, what do you think it means that the girls might finally be at rest?”

That is not a good question for going to bed, I think. Like bringing up a divorce or a personal problem on a postcard. So I give her the brief, easy answer. “That we can let them go, I suppose.”

Thank God, she is so tired and does not push me to say more.

Some nights when I cannot sleep, I lie in bed and play that game Minerva taught me, going back in my memory to this or that happy moment. But I’ve been doing that all afternoon. So tonight I start thinking of what lies ahead instead.

Specifically, the prize trip I’ve as good as won again this year.

The boss has been dropping hints. “You know, Dedé, the tourist brochures are right. We have a beautiful paradise right here. There’s no need to travel far to have a good time.”

Trying to get by cheap this year!

But if I’ve won the prize trip again, I’m going to push for what I want.

I’m going to say, “I want to go to Canada to see the leaves.”

“The leaves?” I can just see the boss making his professional face of polite shock. It’s the one he uses on all the tutumpotes when they come in wanting to buy the cheaper policies. Surely your life is worth a lot more, Don Fulano.

“Yes,” I’ll say, “leaves. I want to see the leaves.” But I’m not going to tell him why. The Canadian man I met in Barcelona, on last year’s prize trip, told me about how they turn red and gold. He took my hand in his, as if it were a leaf, spreading out the fingers. He pointed out this and that line in my palm. “Sugar concentrates in the veins.” I felt my resolve to keep my distance melting down like the sugar in those leaves. My face I knew was burning.

“It is the sweetness in them that makes them burn,” he said, looking me in the eye, then smiling. He knew an adequate Spanish, good enough for

what he had to say. But I was too scared yet to walk into my life that bold way. When he finished the demonstration, I took back my hand.

But already in my memory, it has happened and I am standing under those blazing trees—flamboyants in bloom in my imagination, not having seen those sugar maples he spoke of. He is snapping a picture for me to bring back to the children to prove that it happens, yes, even to their old Mama Dedé.

It is the sweetness in them that makes them burn.

Usually, at night, I hear them just as I’m falling asleep.

Sometimes, I lie at the very brink of forgetfulness, waiting, as if their arrival is my signal that I can fall asleep.

The settling of the wood floors, the wind astir in the jasmine, the deep released fragrance of the earth, the crow of an insomniac rooster.

Their soft spirit footsteps, so vague I could mistake them for my own breathing.

Their different treads, as if even as spirits they retained their personalities, Patria’s sure and measured step, Minerva’s quicksilver impatience, Mate’s playful little skip. They linger and loiter over things.

Tonight, no doubt, Minerva will sit a long while by her Minou and absorb the music of her breathing.

Some nights I’ll be worrying about something, and I’ll stay up past their approaching, and I’ll hear something else. An eerie, hair-raising creaking of riding boots, a crop striking leather, a peremptory footstep that makes me shake myself awake and turn on lights all over the house. The only sure way to send the evil thing packing.

But tonight, it is quieter than I can remember.

Concentrate, Dedé, I say. My hand worries the absence on my left side, a habitual gesture now. My pledge of allegiance, I call it, to all that is missing. Under my fingers, my heart is beating like a moth wild in a lamp shade. Dedé, concentrate!

But all I hear is my own breathing and the blessed silence of those cool, clear nights under the anacahuita tree before anyone breathes a word of the future. And I see them all there in my memory, as still as statues, Mamá and Papá, and Minerva and Mate and Patria, and I’m thinking something is missing now. And I count them all twice before I realize-it’s me, Dedé, it’s me, the one who survived to tell the story.

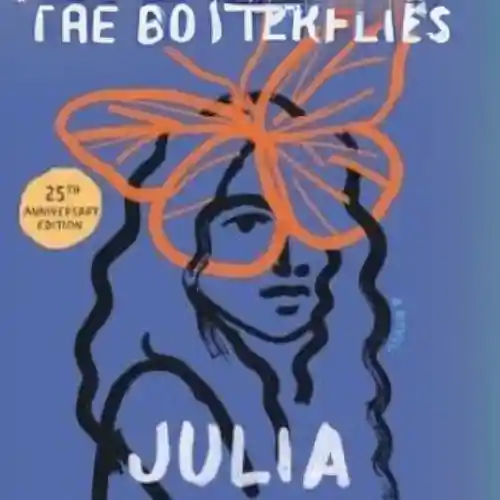

A Postscript

On August 6, 1960, my family arrived in New York City, exiles from the tyranny of Trujillo. My father had participated in an underground plot that was cracked by the SIM, Trujillo’s famous secret police. At the notorious torture chamber of La Cuarenta (La 40), it was just a matter of time before those who were captured gave out the names of other members.

Almost four months after our escape, three sisters who had also been members of that underground were murdered on their way home on a lonely mountain road. They had been to visit their jailed husbands who had purposely been transferred to a distant prison so that the women would be forced to make this perilous journey. A fourth sister who did not make the trip that day survived.

When as a young girl I heard about the “accident,” I could not get the Mirabals out of my mind. On my frequent trips back to the Dominican Republic, I sought out whatever information I could about these brave and beautiful sisters who had done what few men—and only a handful of women – had been willing to do. During that terrifying thirty-one-year regime, any hint of disagreement ultimately resulted in death for the dissenter and often for members of his or her family. Yet the Mirabals had risked their lives. I kept asking myself, What gave them that special courage?

It was to understand that question that I began this story. But as happens with any story, the characters took over, beyond polemics and facts. They became real to my imagination. I began to invent them.

And so it is that what you find in these pages are not the Mirabal sisters of fact, or even the Mirabal sisters of legend. The actual sisters I never knew, nor did I have access to enough information or the talents and inclinations of a biographer to be able to adequately record them. As for the sisters of legend, wrapped in superlatives and ascended into myth, they were finally also inaccessible to me. I realized, too, that such deification was dangerous, the same god-making impulse that had created our tyrant.

And ironically, by making them myth, we lost the Mirabals once more,

dismissing the challenge of their courage as impossible for us, ordinary men and women.

So what you will find here are the Mirabals of my creation, made up but, I hope, true to the spirit of the real Mirabals. In addition, though I had researched the facts of the regime, and events pertaining to Trujillo’s thirty- one-year depotism, I sometimes took liberties—by changing dates, by reconstructing events, and by collapsing characters or incidents. For I wanted to immerse my readers in an epoch in the life of the Dominican Republic that I believe can only finally be understood by fiction, only finally be redeemed by the imagination. A novel is not, after all, a historical document, but a way to travel through the human heart.

I would hope that through this fictionalized story I will bring acquaintance of these famous sisters to English-speaking readers.

November 25th, the day of their murder, is observed in many Latin American countries as the International Day Against Violence Towards Women. Obviously, these sisters, who fought one tyrant, have served as models for women fighting against injustices of all kinds.

To Dominicans separated by language from the world I have created, I hope this book deepens North Americans’ understanding of the nightmare you endured and the heavy losses you suffered—of which this story tells

only a few.

iVivan las Mariposas!

To those who helped me write this book

Bemardo Vega

Minou

Dedé

Papi

Chiqui Vicioso

Fidelio Despradel

Fleur Laslocky

Judy Yamall

Shannon Ravenel

Susan Bergholz

Bill

La Virgencita de Altagracia

mil gracias

William Galvan’s Minerva Mirabal, Ramon Alberto Ferreras’s Las Mirabal, as well as Pedro Mir’s poem “Amén de Mariposas,” were especially helpful in providing facts and inspiration.

a cognizant original v5 release october 14 2010