I learned that the night before a protest, it’s impossible to sleep. I didn’t toss or turn, I just lay at on my back staring into the darkness, my mind darting from thought to thought, from friend to friend, from brother to mother, from hashtag to hashtag. And in the morning, I wasn’t groggy or grumpy, or even sleepy. I was sick. And it was a good thing that I hadn’t planned on going back to school until Monday, because I spent what seemed like hours in the bathroom shitting nerves. And pizza.

Once I nally made it out to the kitchen, my mother—who had taken the day off—was sitting at the table in her robe, sipping coffee, staring at the television.

“Good morning,” she said. en, noticing my hand rubbing so circles on my stomach, her voice went into instant worry. “What’s the matter?”

“Not feeling too well,” I said, easing into a seat.

“Should I take you back to the hospital?”

“No, no, I don’t think it’s anything like that.” I hoped.

Ma got up, pressed the back of her hand against my forehead, then to my neck. “No fever. at’s a good sign,” she said, relief in her voice. She grabbed the kettle off the stove, lied it to make sure there was water in it, then set it back down. She turned on the ame. “I’ll make you some mint tea,” she added, reaching up into the pantry to grab a tea bag and a mug. “I bet it’s just your nerves. You keep ’em buried in your belly. Got that from your

daddy.”

“What you mean?”

“I mean, whenever you get nervous, your stomach acts crazy,” she said.

“Your father has the same problem. He can eat anything. Seems like his gut is made of steel when it comes to food. But when he gets nervous, he’s a mess.”

I never knew this about my father, maybe because he never seemed like he was too nervous about anything. I mean, besides that story he told me about him shooting Darnell Shackleford, I had never even known my father to show any sign of fear. But this new information got me thinking. He was sick earlier in the week. Said something didn’t agree with his stomach, so maybe the thing that didn’t agree with his gut was . . . what happened to me.

Police brutality. Maybe. Or maybe it was just seeing me in pain. Or maybe even knowing somewhere deep in the pit of his belly that I was innocent.

Ma set the tea in front of me, then sat back down. We both sipped from our mugs and watched the news. Everybody was talking about the upcoming protest, which was scheduled to start at ve thirty. Clips of military vehicles rolling past as reporters talked about “hopes for a peaceful demonstration.” Police officers already dressed in military gear. I had seen it before. I had seen it all the other times there were protests in other parts of the country, other cities, other neighborhoods. I’d heard Spoony talk about it, because he and Berry had taken buses to other cities to march. He had been tear gassed before and told me it was like someone rubbing an onion on your eyeballs, and then pouring hot gasoline down your throat. e words “riot” and “looters” were being thrown into the conversation too, my picture next to Galluzzo’s ashing across the screen, the footage of the arrest, looping. Experts arguing, is isn’t the first time this has happened. But until we have an honest conversation about prejudice and abuse of power in law enforcement, it won’t stop, and, Unless you’ve been a police officer, there’s no way to know how difficult a job it is. Law enforcement isn’t perfect, but there are more good examples than bad.

“Is Dad coming?” I asked, holding the cup up. e steam snaked up into my nose.

Ma pursed her lips. “Baby, I don’t even know. I woke up in the middle of the night, realizing he wasn’t in the bed. When I got up to check on him, I found him standing at your door, peeking in at you, like he used to do when you were a baby. I didn’t disturb him. I just crept back to the room. I was surprised he even made it up this morning for work, let alone a march.”

“I was awake. I wish he would’ve knocked,” I said, also surprised—that he had been watching me in the rst place. I wondered . . . maybe he was reliving what it was like to leave me every day to be a cop. What it was like to love something enough to do anything to come back to it.

“Yeah, well, you know your father.”

“Did he say something about it this morning?”

“No. He just went to work early, didn’t say much of anything. Kissed me as usual and told me to be safe, but that was it. So we’ll see.”

e smell of mint suddenly turned my stomach. Or maybe it was what my mother had just said, which made me imagine that Dad had given her “the talk.” You know, Never fight back. Never talk back. Keep your hands up.

Keep your mouth shut. Just do what they ask you to do, and you’ll be fine.

Dad’s guide to surviving the police. Dad’s guide to surviving a protest. Dad’s guide to surviving . . . Dad. Whatever it was, my stomach started hiccuping again, jumping around like I was possessed by something nasty. I set my mug down on the table and ran back to the bathroom.

Once I made sure it was safe to leave the toilet, I needed to go lie down.

Who knew that lying down for a week could make you so tired? But before climbing back in the bed, I got on my knees and reached underneath it, trying to grab a shoe box that I had pushed way too far back. Argghkk—that hurt. Once I’d nally swatted it close enough to grip, I pulled the raggedy box from under the bed frame and set it on the mattress. I popped the top off and started digging through the hundreds of pieces of torn newspaper.

My Family Circus tear-outs. I don’t really know why I suddenly had to see them now, except maybe they were a distraction I could really, really count on. I mean, I could’ve drawn something myself, but whatever was inside was what was going to come out, so it would’ve probably been another picture of someone getting slammed, or something like that. So e Family Circus was better. Easier.

It had been a few years since I had looked at any of them, and lea ng through them transported me back to sitting across from my father, licking marshmallows off the top of hot chocolate, reading them for the rst time.

Man, that seemed like a lifetime ago. Even thinking about it was like thinking about someone else’s life, not my own. I mean, the innocence of it all seemed almost silly now. To think that life could always be as good as breakfast with your family and sharing the newspaper with your dad, looking up to him, imagining that one day you’d read the whole entire paper and drink coffee too. To think that my life could be as perfect as Billy’s.

I ipped through a dozen tear-outs, then another, and then I froze.

Between my ngers was the one of Billy talking to his mother. It read, First

thing you need to know is, I didn’t do it. I put it to the side and pulled out another. is one showed the little boy standing at his father’s bed. His father is just waking up, and the little boy says, Put your glasses on, Daddy, so I can remember who you are. And another that simply said, Mommy, when am I gonna reach my full potential? ey were still boring. Still not funny at all. But I kept reading them, a simple and safe white family framed in a circle, like looking into their lives through a telescope or binoculars from the other side of the street. From a different place. From a place . . . not always so sweet. I laid back in the bed and continued pulling them from the box, one by one, until nally I dried off to sleep.

But it was only a short nap because before I knew it, Spoony was knocking on my door.

“Li’l bruh, you gotta get up, man. It’s almost time to go,” he said, cracking the door, peeking in before pushing it wide open, just as everyone had done at the hospital. He was dressed in all black. Black hoodie. Black jeans. Black boots. A megaphone in his hand. Damn. “Get dressed,” he said, followed by, “What in the world were you doing?”

I looked around at all the scraps of comic strips littering the bed.

“Nothing, man,” I said, sitting up. “I’ll be ready in a sec.”

I put on all black too—just seemed like the right thing to do—and met Ma, Spoony, and Berry in the kitchen. Berry was also dressed in black. My mother, she had on her usual mom jeans, sweater, a light jacket, and sneakers. Oh, and a fanny pack. She was ready. ey all were. But I needed to go to the bathroom, one more time.

“Get it out, baby,” my mother said, explaining to Spoony that I had been sick all day, like that was any of his business. But that’s moms for you. Funny thing is, I didn’t even have to go. ere was something else I wanted to do.

In the bathroom, I stood at the sink, staring at my re ection. I brought my hands to my face and slowly peeled the tape and bandage back, revealing my nose. Still swollen. ere was a knot on the top—a lump that changed the way my whole face looked. I turned my head sideways—bump looked even worse. I hated that damn bump, but I didn’t want people to see me all bandaged up like that. Not because I was embarrassed. Well, I was, a little.

But more importantly, I wanted people to see me. See what happened. I wanted people to know that no matter the outcome, no matter if this day ended up as just another protest and Officer Galluzzo got off scot-free, that I

would never be the same person. I looked different and I would be different, forever.

When I returned to the kitchen, my mother instantly began to tear up.

My brother nodded, balled his right hand into a st, and extended it toward me. “You ready?”

I bumped my st to his. “Yeah, I’m ready.”

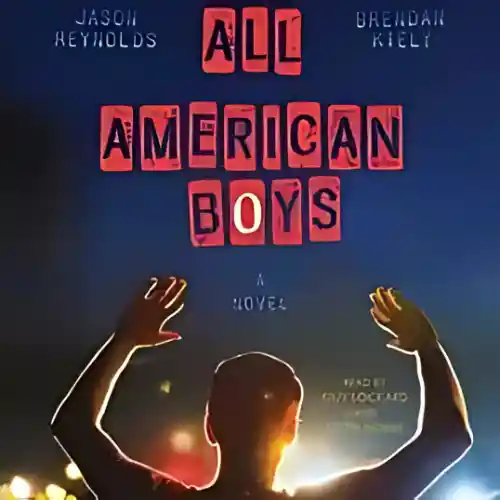

I couldn’t believe it. We couldn’t even get all the way to Fourth Street because of all the people. So Ma parked on Eighth and we walked down to join the crowd, English, Carlos, and Shannon all texting me telling me that they were in front of Jerry’s. We wove in and out of the herd—so many people, mostly strangers, but everyone there for the same reason. It was unreal. Lots of people held up signs. Police officers lined the streets, creating a kind of wall, containing us. ere were these huge trucks, like road tanks, blocking us at either end, locking us into a seven- or eight-block rectangle. e newspeople were there as well, men in gray suits and blue ties, holding microphones in front of some kids I recognized from school.

“Stay close,” Spoony said as we pushed down Fourth Street. He held my mother’s hand, and I kept a hand on her shoulder as he and Berry led the way. I was glad they had done this before, because my heart felt like it had grown feet and was trying to run away from my body. As we moved through, eventually people started to recognize me, and the crowd began to split open, making a clearer path for us.

“I see Carlos!” I said to Spoony, raising my voice to be heard.

“ere’s English over there!” Berry shouted back, pointing to the right.

And there they were, my friends—my brothers—standing in front of Jerry’s, holding big white poster boards, RASHAD IS ABSENT AGAIN TODAY written in bold black marker. ey went crazy when they saw us—Shannon waving us forward like we were the royal family or something, making sure to let people know to let us through. When we nally got to them, they each hugged me, then my mom. I looked out at the crowd. People, young, old, black, white, Asian, Latino, more people than I could count. It was straight out of an Aaron Douglas painting, except there were faces. Faces everywhere. My teachers, Mr. Fisher and Mrs. Tracey. Tiffany, who gave me

a look, both happy and sad. Latrice Wilkes. Oh! My comrades from ROTC, and because it was Friday, uniform day, they were dressed head to toe. Some of the basketball players. Football players. Neighborhood people. Pastor Johnson, in a suit, but this time, instead of a Bible, he held a sign up that said, RASHAD IS ABSENT AGAIN TODAY, BUT GOD IS NEVER ABSENT. Katie Lansing was there. I didn’t see Mrs. Fitzgerald, but I wouldn’t have wanted her out there, even though I was sure she was tough enough to handle it. Even Clarissa was there, which was amazing. I waved to her, but the crowd seemed to think that I was waving to everybody, and so they all cheered for me, which was overwhelming. I knew it wasn’t just about me. I did. But it felt good to feel like I had support. at people could see me.

e chant was a simple one. I’m not sure exactly who came up with it. It just sort of started in the middle and rippled through the crowd. “Spring-

eld P-D, we don’t want brutality! Spring- eld P-D, we don’t want brutality!”

We chanted it, no, we screamed it, at the top of our lungs, over and over again as we started marching toward Police Plaza 1. Spoony shouted it into the megaphone, and he wasn’t the only one. Everyone was on the same page, chanting the same thing as we moved down Main Street. Me, Spoony, Carlos, English, Berry, and Shannon were in the front of the crowd, and all of a sudden, our arms locked and we were leading the way like—the image came to me of raging water crashing against the walls of a police dam.

Marching. But it wasn’t like I was used to. It wasn’t military style. Your le!

Your le! Your le-right-le! It wasn’t like that at all. It was an uncounted step, yet we were all in sync. We were on a mission.

And as we approached the police station, standing on the steps outside Police Plaza 1 was my father. Spoony slapped my arm and nodded toward Dad, totally surprised. My brother raised an eyebrow at me. I raised one at him. “Whatttttt?” en we both grinned at the exact same time. Ma, of course, was crying. Instantly. She had been doing a pretty good job at keeping it together, but seeing my father standing there waiting for us broke her. He jogged down the steps and met us with hugs. He didn’t say anything.

Just hugged and locked arms with us as we turned around and faced the crowd, still chanting, “Spring- eld P-D, we don’t want brutality!”

Spoony gave Berry the megaphone and she started chanting through the speaker, even louder than he had. He dug in his backpack and pulled out the papers, the same papers he’d showed us the night before at the kitchen table,

as Berry slowly got down on the ground. She lay at on her back, the megaphone still to her mouth, still chanting. Spoony followed suit. He nodded to me. My father looked on, uneasy, as me, Carlos, Shannon, and English all laid down. My mother leaned in to him and whispered something. e confusion slowly slid from his face, and he took his wife’s hand and helped her lower herself to the ground. en he joined us as well.

And the people in front of the crowd followed suit, realizing what was happening. e die-in was beginning, and like dominoes, the crowd began to drop, each person, young and old, lying at on the dirty pavement, the police officers all around us in riot gear, their hands on their weapons, afraid and perplexed.

“Ladies and gentlemen!” Berry shouted through the megaphone. “Ladies and gentlemen!” e chanting died down. “We are here, not for Rashad, but for all of us! We are here to say, enough is enough! We are here to say, no more! No more!” Spoony gave the rst paper to her. And into the megaphone, she began.

“is is a roll call! Sean Bell!” en she followed with “Absent again today! Oscar Grant! Absent again today! Rekia Boyd! Absent again today!

Ramarley Graham!” She paused, and at that point the rest of us knew exactly

what to do.

“Absent again today!”

“Aiyana Jones!”

“Absent again today!”

“Freddie Gray!”

“Absent again today!”

“Michael Brown!”

“Absent again today!”

“Tamir Rice!”

“Absent again today!”

“Eric Garner!”

“Absent again today!”

“Tarika Wilson!”

“Absent again today!”

And Spoony kept feeding Berry the papers, one aer another, as she continued to read down the list of unarmed black people killed by the

police. And I laid there on the hard concrete, for the second time in a week, tears owing down my cheeks, thinking about each one of those names.